Lost in Transition: "Bonhoeffer" and the Swastika

In this follow-up report, we explore the true biography and teachings of anti-Nazi cleric Dietrich Bonhoeffer, an intellectual godfather of Liberation Theology...

Last Friday, I published my initial report on Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin (dir. Todd Kormanicki, 2024), the biography of a Lutheran cleric martyred as a member of the anti-Nazi resistance in Germany, and how, shockingly, the Bonhoeffer family, the International Bonhoeffer Society, and the film’s cast were unified in publicly denouncing a film marketing campaign catered to Christian Nationalist audiences. This is a complex story that spans more than a century and two continents, diving as deeply into the nuances of Protestant theology as the Weimar and Wartime German government systems.

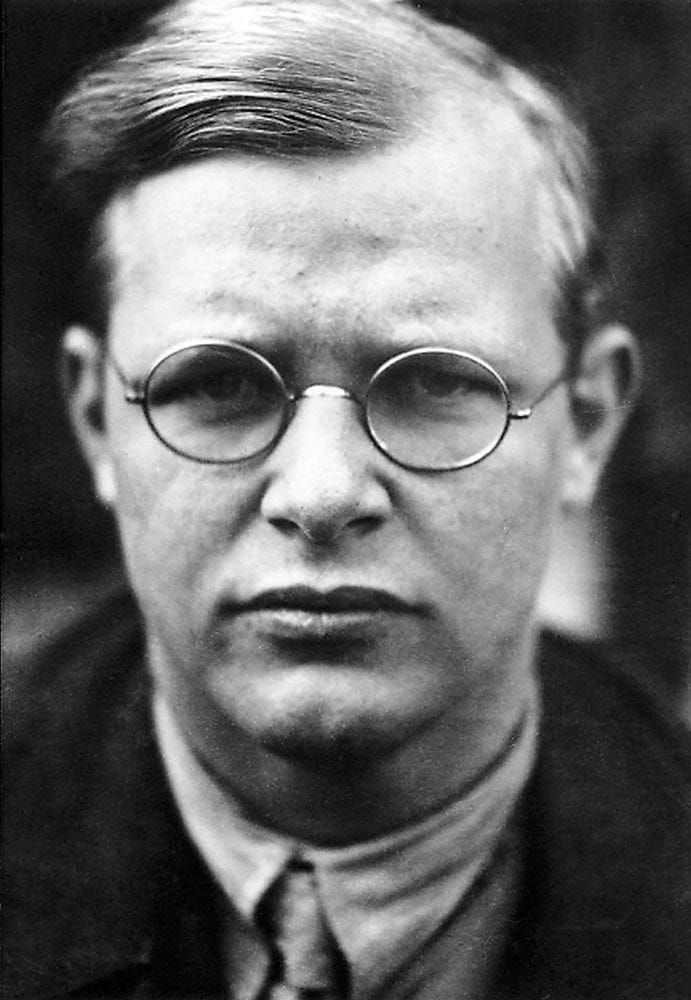

Dr. Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s (1906-1945) Dialectical Theology begins with his 1927 Divinity dissertation Sanctorum Communio, a considerable exploration of what “the Church” means in terms of ecclesiology. Ecclesiology is a kind of socio-theology where the author explores the material presence of the Church as a community organization alongside the Gospel teachings about the subject.

Read the Entire Three-Part Series:

There are two distinctive elements to consider particularly in this work. First, the firm grounding in material understanding of the Church from a sociological perspective and, secondly, his indictment of the institutional Lutheran Church as “bourgeois.” Bonhoeffer predicates his perception of the Church in materialist political economy and launches from that point a denunciation of the manner by which it had calcified and become institutionalized. Bonhoeffer was part of a generation of scholars and philosophers who had to confront the aftermath of the Great War and consider the implications of Europe’s implosion into bloodshed despite being a landmass previously known as “Christendom.” Like his contemporary Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises, Bonhoeffer’s Theological Lost Generation was traumatized by the war and, quite rapidly, the abdication of the monarchy, which had played a major role in German Christianity.

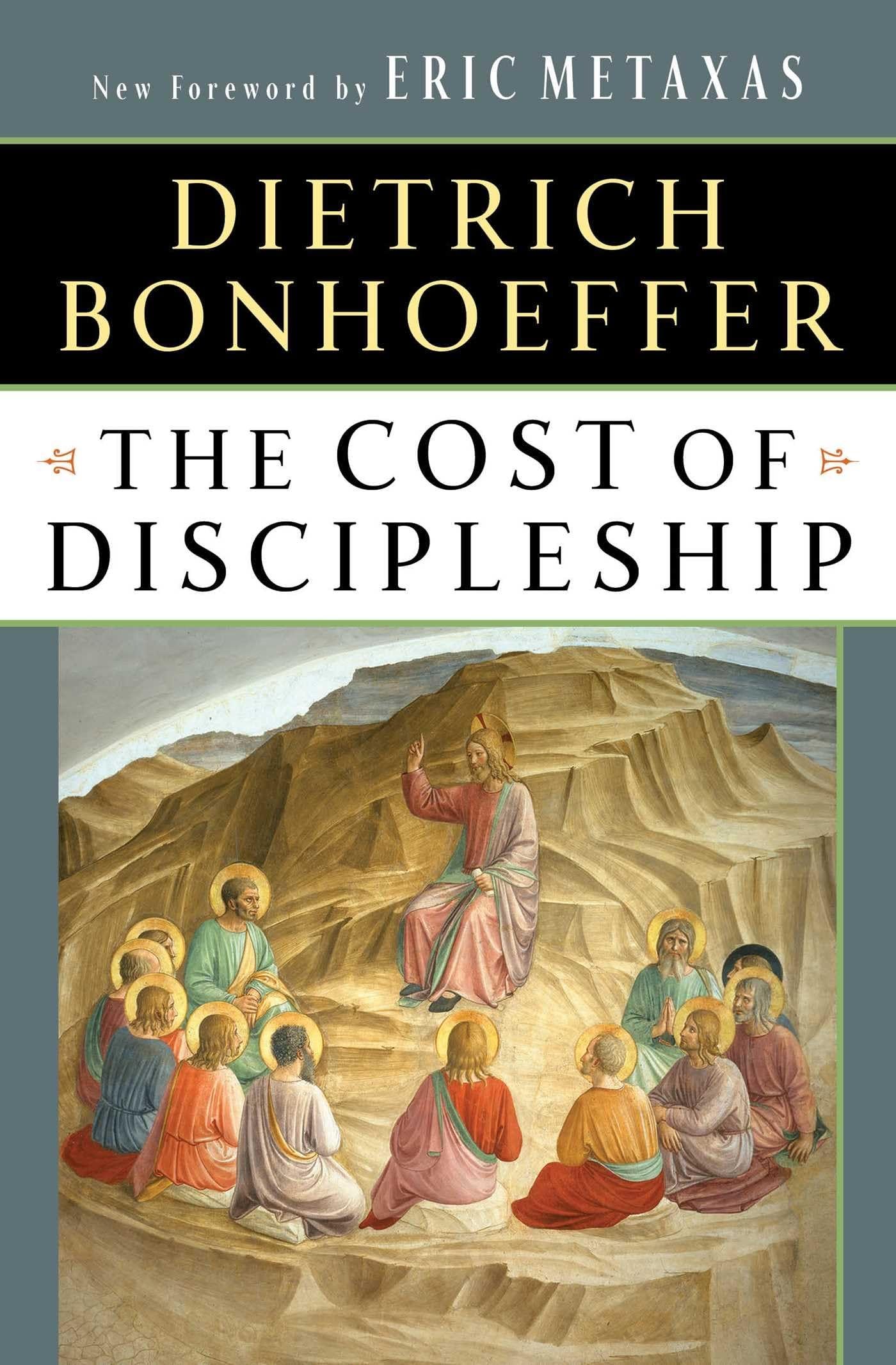

The Cost of Discipleship (1937), Bonhoeffer’s treatise on grace, is a thorough repudiation of clericalism. He traces out a preliminary theory of the Preferential Option for the Poor within Latin American Liberation Theology. That part would prove to be so troublesome for the Vatican in the 1980s by arguing that “cheap grace” is opposed to “costly grace,” the experience of the downtrodden and oppressed. There are clear traces of influence from the Black Church and the American Social Gospel movement of Walter Rauschenbusch that the author had been exposed to during his 1930 Sloane Fellowship studies at New York’s Union Theological Seminary.

Abyssinian Baptist Church’s contemporary choir performs “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

At Union and Harlem’s historic Abyssinian Baptist Church, he had studied the Social Justice Gospel as espoused by Rev. Adam Clayton Powell. (As a side-note to be revisited later, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. would one day become a stalking horse for National Review Editor William F. Buckley, Jr. in a fashion culminating with court proceedings and attempts to influence grand jury investigations in the later 1950s.)

These summaries by no means constitute a thorough-going analysis or description of these theological works. However, they likewise demonstrate a general orientation towards a Continental philosophy and Dialectical Theology, meaning having firm anchorage in the Religious Left tradition.

In my previous column on the biopic’s devious marketing strategy, I highlighted the subtle role of one Eric Metaxas, a Christian Nationalist broadcaster and ideologue with deep allegiances to Donald Trump. Here is his July 2024 conversation with Vice President-elect JD Vance, an exchange peppered with extreme paranoia masking ruthless cynicism. Bonhoeffer is referenced in the Project 2025 manifesto, a document Vance had a hand in authoring, and I suspect its references to “cheap grace” can be attributed directly to Metaxas and his ilk.

Bonhoeffer’s protests against Hitler extended from simple public statements and civil disobedience to affiliation with a newly-formed Confessing Church, which supported a coup plot from within the officer’s corps. Implanting themselves amongst the German Abwehr intelligence agency, the conspirators coordinated with officers in order to attempt the assassination of Hitler. Bonhoeffer was playing a key role by smuggling intelligence and communiques to London via the diplomatic pouch and Parliamentarians like his ally the Anglican Rev. George Bell. The mild clergyman was functionally a double-agent within the Third Reich, a powerful story of espionage during the Second World War.

Yet he was a nuanced thinker whose understanding of violence was far more complex than that proffered by either Metaxas or Vance. They by contrast subscribe to a far more simplistic, authoritarian, and frightening vision of theology’s role in the public square, a revanchist settler colonial religion based upon a siege mentality. There is no correlation between Bonhoeffer’s thought and theirs. The attempt to superimpose Bonhoeffer into a Litany of Christian Nationalist Saints is extremely disturbing because of how it warps his biography to serve that violent cis-/hetero-sexist agenda.