Why hasn’t the undisguised public revulsion at President Donald Trump’s DOGE coup alongside tech oligarch Elon Musk congealed into a serious political mobilization equivalent to the Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam War era of the 1960’s?

Why, more than six months after the most humiliating defeat, hasn’t the public disgust with the Democratic Party created the opportunity for a genuine palace coup where the leadership is swept aside for not simply Progressives like AOC but also the much wider majority of unaffiliated or legally-disenfranchised voters in order to bring about a return to certain decency and sanity?

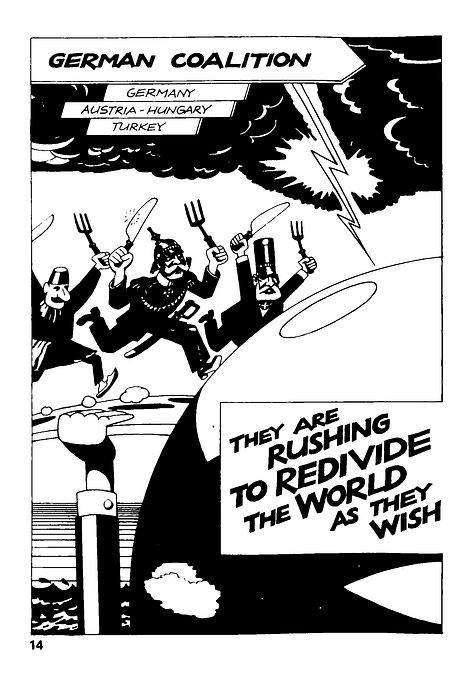

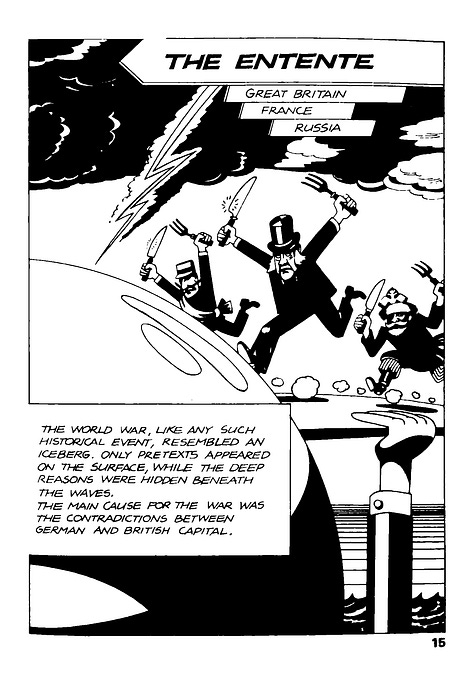

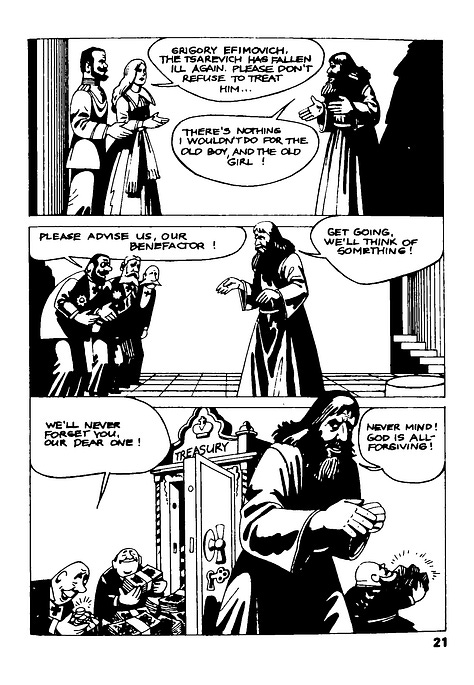

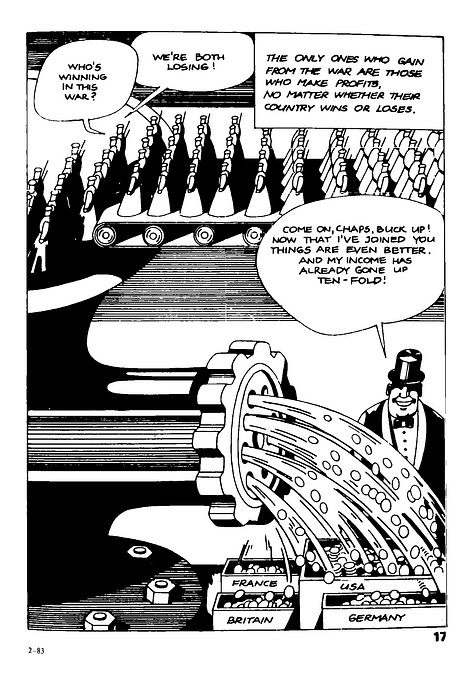

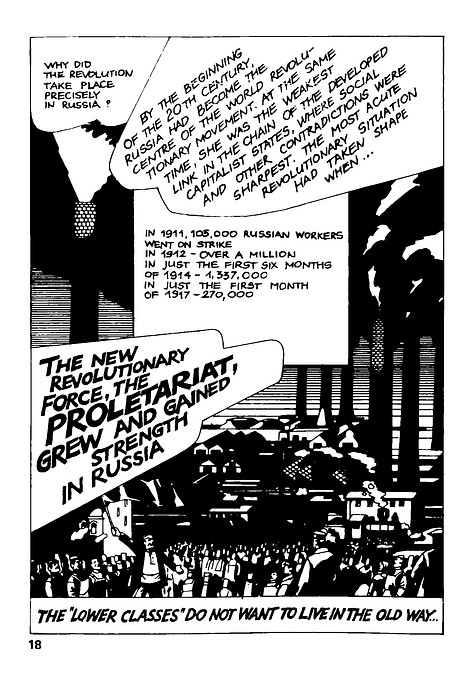

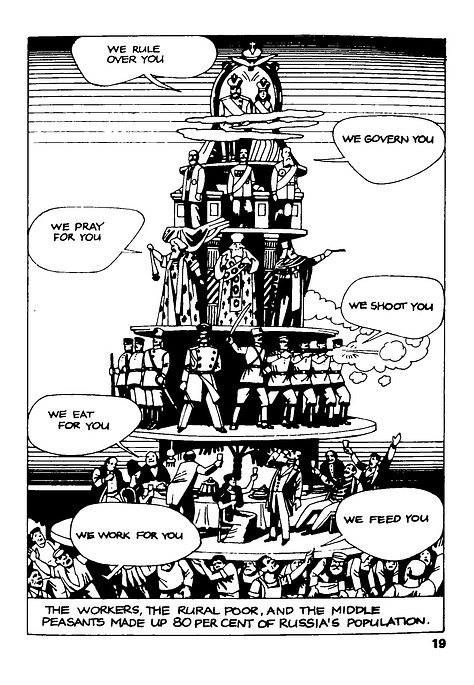

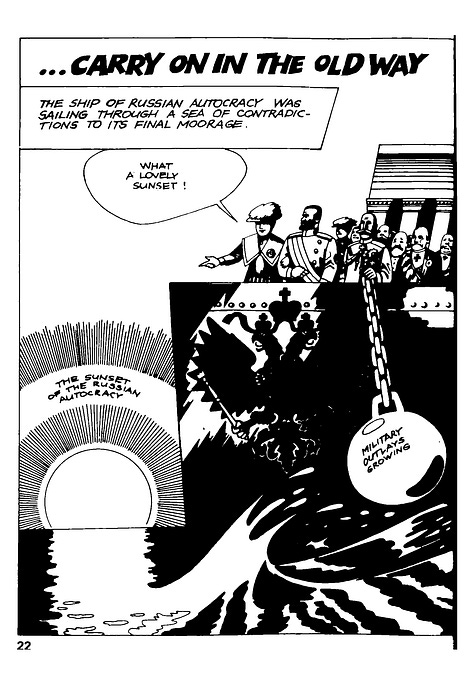

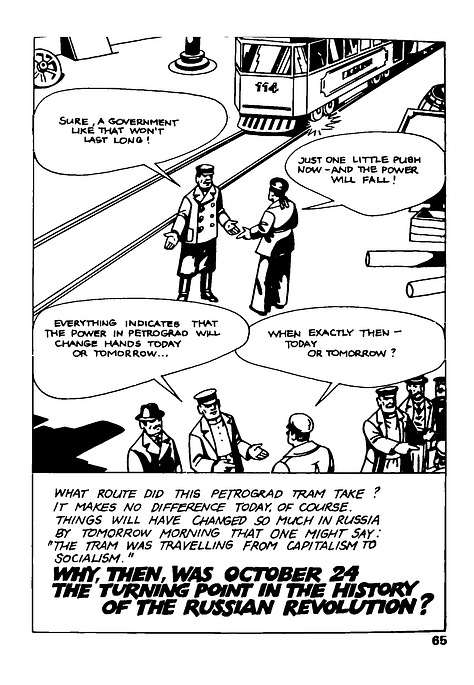

In a revived graphic novel, originally issued in 1985 by the Soviet Progress Publishers and now republished by me in both paper and digital format on Amazon Kindle, the Soviet Communist Party set about retelling the story of the Russian revolution. With artwork clearly indebted to German Expressionist filmmakers and narrative methods dating back to the theoretical works of Soviet Silent Era artists like Sergei Eisenstein, we see a revolution as told from the perspective of the working class as opposed from the Bolshevik leaders who were commonly subject to their own Cults of Personality. That dearth of the overly-gratuitous worship for any one individual character, the notion of the class as the protagonist, represents the notion of consciousness moving from in itself to for itself.

To begin with a mild confession, I stepped into Marxism innocently, almost as if I had located a dog pile, when my original Film History classes at Rhode Island College required we watch all the classics of Soviet cinema and read their major theoretical articles. Writers/directors/critics like Lev Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and other early Soviet artists had seriously contemplated the completely novel idea of trying to make the proletariat itself function as the protagonist in their films, hence why films like Potemkin only feature abstract personages as opposed to the deep character melodramas seen contemporaneously in Hollywood.

I thought that was completely barmy at first, and not only because the Cold War’s relatively-recent extinction meant Foucault-inclined postmodern and post-structural theory seemed to perfectly compliment whatever inherited “End of History” biases we had been programmed with as middle schoolers.

Even the instructor, the utterly brilliant Film Historian Dr. Kaye Kalinak, had to acknowledge the Marxian novelty had a shelf life; within less than a decade of producing these most extraordinary diadems of silent cinema, Stalin implemented the mandate of Socialist Realism, resulting in propaganda films embracing the exact Romantic tropes shunned by the silent auteurs.

Consider the following clip from The Fall of Berlin (dir. Mikhail Chiaureli, 1949), the infamous war epic that pompously stages Joseph Stalin fictitiously landing his plane on the airfield as the Nazis surrender to the victorious Red Army.

Yes, four years after the war, Stalin made a movie about how he personally witnessed the Fall of Berlin and oversaw the Red Army capture of the city. Hitler and his cabal gather, almost like Western Gentile Learned Elders, and grovel in his throne room. The Führer himself is so cartoonish that a Sith Lord from Star Wars honestly seems more evil than the man responsible for the greatest crime against peace in history up until that point.

As something that had a Start-and-End Date, Soviet cinema ended with emphasis upon the command economy being twinned with censorship. Soviet cinema is basically marked by three sections of great art followed by solid decades of terrible ethnic comedies and wretched musicals. For the good parts, there is the Silent period, the Khrushchev thaw, and then finally Glastnost, which all just coincidentally came when the Soviet government introduced various methods of market liberalization. The sterling figures, like Andrei Tarkovsky, were always complete outliers, marginalized and reviled in exchange for horrific musical-comedies set in 19th century Armenia.

Long-form silent films only were beginning to truly develop in 1915, most notably when the despicable war epic Birth of a Nation (dir. D.W. Griffiths) broke records by presenting one of the longest narrative pictures up to that date. Bolshevism was born simultaneous with the long-form narrative cinema text we colloquially call movies. Eisenstein wrote articles about Disney and Griffiths as a colleague and peer with a uniquely different notion on how to tell stories but mutual admiration and respect for their technological innovations; his dearth of comment on the reactionary politics of each respective producer is another topic entirely.

Lenin openly acknowledged in his writings that cinema was going to be an essential item in the propaganda arsenal. And so when the Soviets were finally able to normalize trade relations and import cameras for productions, they were starting to make pictures during the New Economic Policy (NEP) era.1

The tautology suggested by scholarship on Soviet film is that, simply based on how bad the later films got under Stalin, market liberalization is equivalent to press freedom.

We likewise see this in the contrast between movies from the Cultural Revolution and, afterward, not only China’s domestic production but also its foreign picture import box office results. 2

Post-Mao Chinese cinema and, much more importantly, cinema box office financial studies, are complex. Taiwanese cinema, Hong Kong cinema, and other Diasporic artworks no longer exist in the wastebasket as “Western Propaganda” about “Running Dog Imperialists”; China has accounted for a massive percentage of the worldwide economic success for various Western franchises, such as Harry Potter, the aforementioned George Lucas’s storytelling worlds, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Disney productions, and other popular intellectual properties. A Beijing red carpet premiere is now equivalent to one held for a Hollywood production in London, Paris, Cannes, or New York. As someone who has lived for my entire life outside of two college towns, Boston and Providence, cities hosting large Chinese foreign student exchange populations, it is pretty hard to ignore the possibility that some of them happily jet down to Disney World for Spring Break. Do their cousins likewise visit Disney Land Tokyo? China is fully-integrated into a worldwide media ecosphere the Soviets never entered owing to the nuances of the era.

The Khrushchev Thaw, in this way, likewise book-ends Stalin’s tenure and his imposition of Socialist Realism. In the brief period of the Thaw, young auteurs in the Socialist Camp began to import French New Wave ideas and techniques into their work. Classics of world cinema, spanning Prague to Havana, came from this period thanks to relaxed censorship standards. They explored issues like postwar veteran melancholia in fictional pictures about such former members of the Red Army, restated with appropriate gravity for documentary films the serious nature of Auschwitz, and even utilized Western experimental art film methods to contemplate the emerging discourse about socialist humanism. When these various constituents of the Warsaw Pact let the people get too rowdy with this free speech, the Soviets sent in the tanks and censorship laws were restored to previous strictures. Two decades later, Gorbachev implemented the same liberalization methods but refused to suppress the resultant secession from the Socialist Camp.

And yet, in a strange dialectical relationship, something rather extraordinary seems to be yielded.

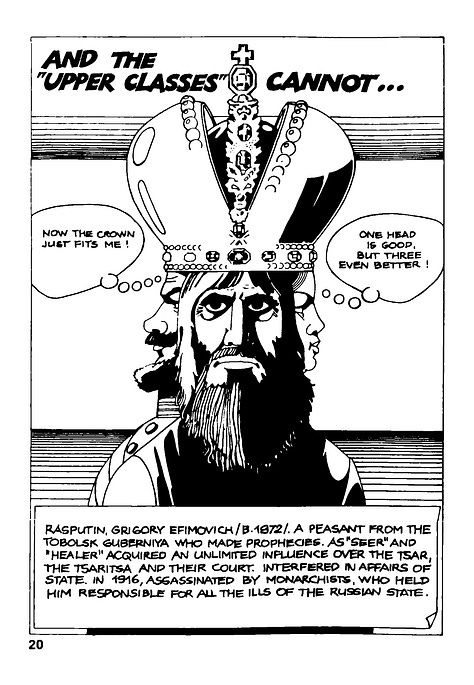

Socialist Realism requires strict censorship and a Great Man of History myth. The Stalin/Trotsky feud was a battle for that position. The fundamental failure of a lot of the books telling the story through a single perspective is the fact it basically replicates the politics of Thomas Carlyle, the ultra-reactionary poet-historian of the French Revolution.3

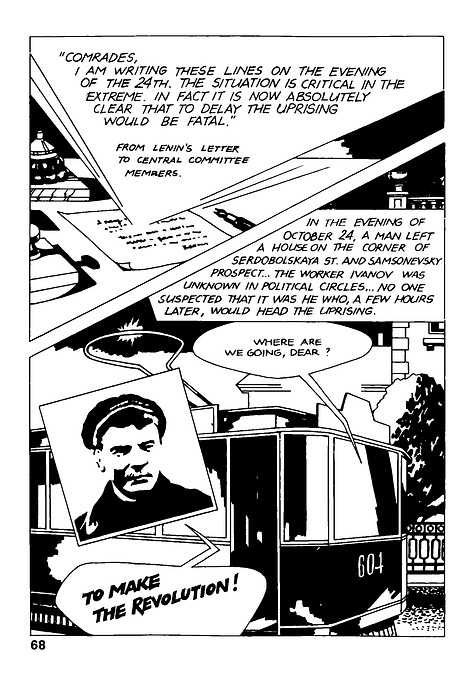

This comic is very intentionally opposed to that, invoking this parallel method of socialist storytelling. It aggregates on the page a tribute to these traditions and notions established originally by the NEP Era silent film directors and their heirs in the Thaw/Glastnost eras.

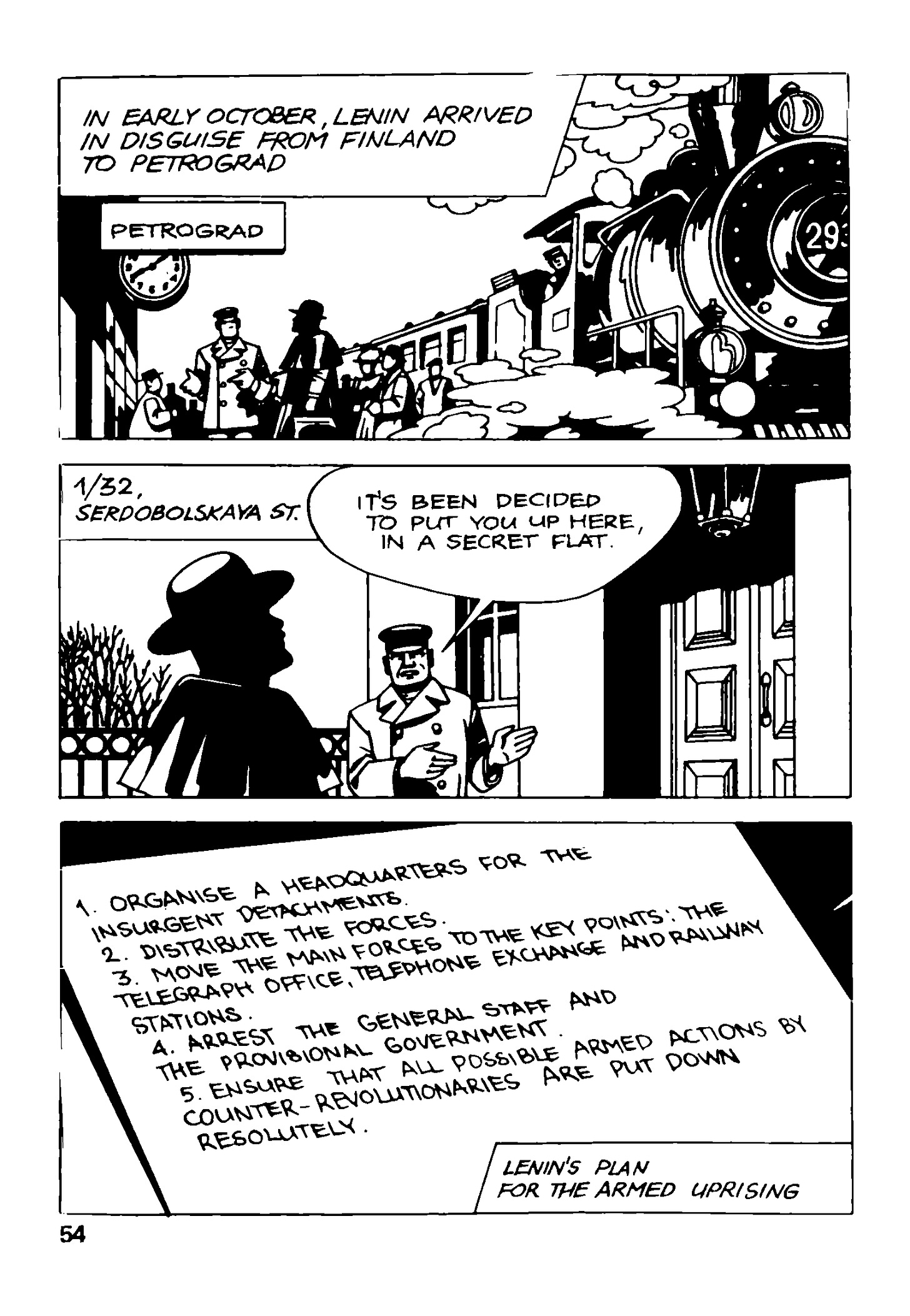

Simply look at how they represent Lenin on this page.

Throughout the book, the anonymous masses are the protagonist, with the Bolsheviks as a guiding force and Lenin as an auxiliary guide.4

Which of course does complete the Möbius strip of online Leninism as less of a politics and more of a fan culture.

This book really laid out what it would look like for a social awakening over war, austerity, and heightened chauvinist revanchism to transition into a full-on movement that can become a political force.

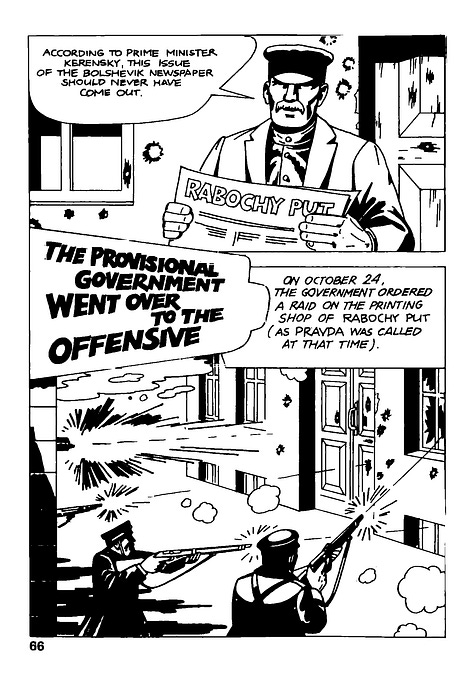

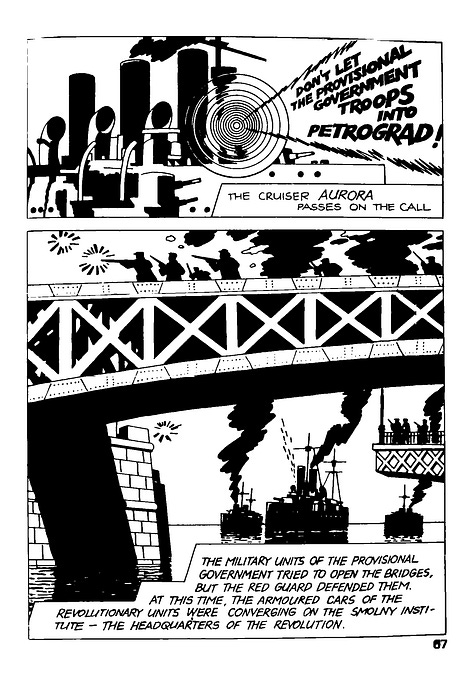

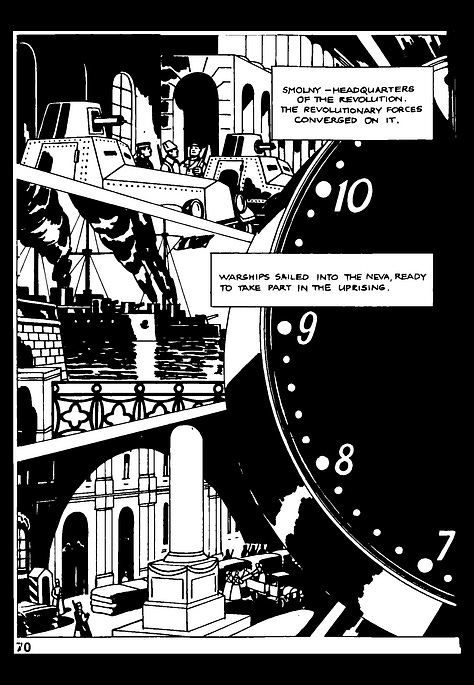

You see the level of work it took for the Bolsheviks to succeed and it is extremely impressive to see a rendition on the page, freed of so many constraints that otherwise hindered a movie like Reds (dir. Warren Beatty, 1981) from being able to give a wide-spectrum panorama view of the October revolution. Don't get me wrong, the movie rules, but they were incapable of staging the cannon firing of the cruiser Aurora, the rebellion of the soldiers and sailors, and the seizure of key power depots like the post office, telephone/telegraph service, and the other rather boring government offices where Warren Beatty can't necessarily stage anything interesting happening.

Compare these nine pages with Beatty’s staging. There’s simply no comparison.

My hope in reviewing and reviving this book is to further perpetuate its ideas. I have personally custom-edited the Kindle ebook version to make it interactive and most accessible for readers, with plenty of close-ups and dollies trying to mimic the best of the aforementioned Silent directors. This interactive opportunity is a unique one for readers and I hope you will enjoy the immersive viewing experience offered via digital technology.

Click the video below to watch an extended silent animated version of the book.

The NEP era is the most complicated controversy in Communist politics excepting perhaps who should have been the actual heir of Lenin. Basically stated, the NEP allows a certain amount of private capital and capitalist relations to exist in the socialist economy in order to build up the productive forces. In China, where they have been running a super-amped version of the NEP since Deng Xiaoping took power, class stratification exists alongside other challenges, including matters like Han Great Nation Chauvinism, access to welfare and government services in the impoverished countryside as opposed to the wealthy coastal cities where all the major manufacturing job opportunities exist, the larger erosion of the old Mao-era Iron Rice Bowl welfare state, and the still-present challenges with religious extremism in the most western provinces of the country.

Furthermore, there is a voluntary desire on the part of Hollywood to curry favor with the Mainland through various symbolic pro-Standardized Chinese gestures. For instance, the out-of-the-blue use of Mandarin by Dr. Yueh (played by Chang Chen) in Dune (dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2021) was a clear bid for the approval of not just Mainland audiences but also the Communist censorship authorities, who appreciate any cinematic endorsement of the One China Policy they can get.

This is not to deny that Joseph Stalin basically built a gigantic comic book wonderland around his talents that seemed to mimic the genius of Bruce Wayne in Batman.

Oh, and yeah, obviously, they don't even mention a certain someone who kinda ran the Petrograd Soviet and then founded the Red Army (no shock, the Soviet Communists never politically rehabilitated Leon Davidovitch; Gorbachev refused to touch that third rail). This comic book universe dictates that, since Great Men don’t exist, Trotsky sure didn’t.